On June 5, 1873, in a letter to The Times, Sir Francis Galton, the cousin of Charles Darwin and a distinguished African explorer in his own right, outlined a daring (if by today’s standards utterly offensive) new method to ‘tame’ and colonise what was then known as the Dark Continent.

‘My proposal is to make the encouragement of Chinese settlements of Africa a part of our national policy, in the belief that the Chinese immigrants would not only maintain their position, but that they would multiply and their descendants supplant the inferior Negro race,’ wrote Galton.

‘I should expect that the African seaboard, now sparsely occupied by lazy, palavering savages, might in a few years be tenanted by industrious, order-loving Chinese, living either as a semidetached dependency of China, or else in perfect freedom under their own law.’

Despite an outcry in Parliament and heated debate in the august salons of the Royal Geographic Society, Galton insisted that ‘the history of the world tells the tale of the continual displacement of populations, each by a worthier successor, and humanity gains thereby’.

A controversial figure, Galton was also the pioneer of eugenics, the theory that was used by Hitler to try to fulfil his mad dreams of a German Master Race.

Eventually, Galton’s grand resettlement plans fizzled out because there were much more exciting things going on in Africa.

But that was more than 100 years ago, and with legendary explorers such as Livingstone, Speke and Burton still battling to find the source of the Nile - and new discoveries of exotic species of birds and animals featuring regularly on newspaper front pages - vast swathes of the continent had not even been ‘discovered’.

Yet Sir Francis Galton, it now appears, was ahead of his time. His vision is coming true - if not in the way he imagined. An astonishing invasion of Africa is now under way.

In the greatest movement of people the world has ever seen, China is secretly working to turn the entire continent into a new colony.

Reminiscent of the West’s imperial push in the 18th and 19th centuries - but on a much more dramatic, determined scale - China’s rulers believe Africa can become a ‘satellite’ state, solving its own problems of over-population and shortage of natural resources at a stroke.

With little fanfare, a staggering 750,000 Chinese have settled in Africa over the past decade. More are on the way.

The strategy has been carefully devised by officials in Beijing, where one expert has estimated that China will eventually need to send 300 million people to Africa to solve the problems of over-population and pollution.

The plans appear on track. Across Africa, the red flag of China is flying. Lucrative deals are being struck to buy its commodities - oil, platinum, gold and minerals. New embassies and air routes are opening up.

The continent’s new Chinese elite can be seen everywhere, shopping at their own expensive boutiques, driving Mercedes and BMW limousines, sending their children to exclusive private schools.

The pot-holed roads are cluttered with Chinese buses, taking people to markets filled with cheap Chinese goods. More than a thousand miles of new Chinese railroads are crisscrossing the continent, carrying billions of tons of illegally-logged timber, diamonds and gold.

The trains are linked to ports dotted around the coast, waiting to carry the goods back to Beijing after unloading cargoes of cheap toys made in China.

Confucius Institutes (state-funded Chinese ‘cultural centres’) have sprung up throughout Africa, as far afield as the tiny land-locked countries of Burundi and Rwanda, teaching baffled local people how to do business in Mandarin and Cantonese.

Massive dams are being built, flooding nature reserves. The land is scarred with giant Chinese mines, with ‘slave’ labourers paid less than £1 a day to extract ore and minerals.

Pristine forests are being destroyed, with China taking up to 70 per cent of all timber from Africa.

All over this great continent, the Chinese presence is swelling into a flood. Angola has its own ‘Chinatown’, as do great African cities such as Dar es Salaam and Nairobi.

Exclusive, gated compounds, serving only Chinese food, and where no blacks are allowed, are being built all over the continent. ‘African cloths’ sold in markets on the continent are now almost always imported, bearing the legend: ‘Made in China’.

From Nigeria in the north, to Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and Angola in the west, across Chad and Sudan in the east, and south through Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique, China has seized a vice-like grip on a continent which officials have decided is crucial to the superpower’s long-term survival.

‘The Chinese are all over the place,’ says Trevor Ncube, a prominent African businessman with publishing interests around the continent. ‘If the British were our masters yesterday, the Chinese have taken their place.’

Likened to one race deciding to adopt a new home on another planet, Beijing has launched its so-called ‘One China In Africa’ policy because of crippling pressure on its own natural resources in a country where the population has almost trebled from 500 million to 1.3 billion in 50 years.

China is hungry - for land, food and energy. While accounting for a fifth of the world’s population, its oil consumption has risen 35-fold in the past decade and Africa is now providing a third of it; imports of steel, copper and aluminium have also shot up, with Beijing devouring 80 per cent of world supplies.

Fuelling its own boom at home, China is also desperate for new markets to sell goods. And Africa, with non-existent health and safety rules to protect against shoddy and dangerous goods, is the perfect destination.

The result of China’s demand for raw materials and its sales of products to Africa is that turnover in trade between Africa and China has risen from £5million annually a decade ago to £6billion today.

However, there is a lethal price to pay. There is a sinister aspect to this invasion. Chinese-made war planes roar through the African sky, bombing opponents. Chinese-made assault rifles and grenades are being used to fuel countless murderous civil wars, often over the materials the Chinese are desperate to buy.

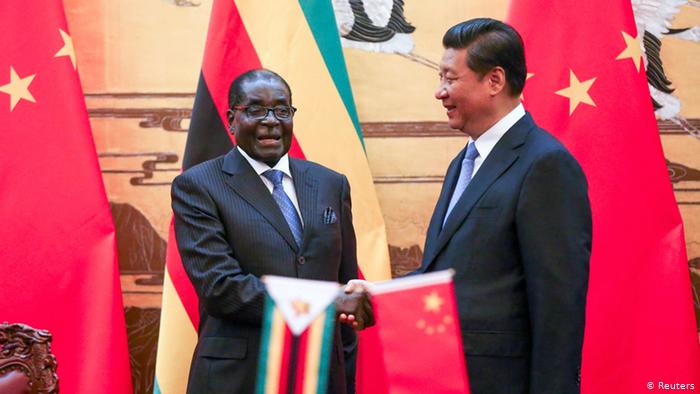

Take, for example, Zimbabwe. Recently, a giant container ship from China was due to deliver its cargo of three million rounds of AK-47 ammunition, 3,000 rocket-propelled grenades and 1,500 mortars to President Robert Mugabe’s regime.

After an international outcry, the vessel, the An Yue Jiang, was forced to return to China, despite Beijing’s insistence that the arms consignment was a ‘normal commercial deal’.

Indeed, the 77-ton arms shipment would have been small beer - a fraction of China’s help to Mugabe. He already has high-tech, Chinese-built helicopter gunships and fighter jets to use against his people.

Ever since the U.S. and Britain imposed sanctions in 2003, Mugabe has courted the Chinese, offering mining concessions for arms and currency.

While flying regularly to Beijing as a high-ranking guest, the 84-year-old dictator rants at ‘small dots’ such as Britain and America.

He can afford to. Mugabe is orchestrating his campaign of terror from a 25-bedroom, pagoda-style mansion built by the Chinese. Much of his estimated £1billion fortune is believed to have been siphoned off from Chinese ‘loans’.

The imposing grey building of ZANU-PF, his ruling party, was paid for and built by the Chinese. Mugabe received £200 million last year alone from China, enabling him to buy loyalty from the army.

In another disturbing illustration of the warm relations between China and the ageing dictator, a platoon of the China People’s Liberation Army has been out on the streets of Mutare, a city near the border with Mozambique, which voted against the president in the recent, disputed election.

Almost 30 years ago, Britain pulled out of Zimbabwe - as it had done already out of the rest of Africa, in the wake of Harold Macmillan’s ‘wind of change’ speech. Today, Mugabe says: ‘We have turned East, where the sun rises, and given our backs to the West, where the sun sets.’

Despite Britain’s commendable colonial legacy of a network of roads, railways and schools, the British are now being shunned.

According to one veteran diplomat: ‘China is easier to do business with because it doesn’t care about human rights in Africa - just as it doesn’t care about them in its own country. All the Chinese care about is money.’

Nowhere is that more true than Sudan. Branded ‘Africa’s Killing Fields’, the massive oil-rich East African state is in the throes of the genocide and slaughter of hundreds of thousands of black, non-Arab peasants in southern Sudan.

In effect, through its supplies of arms and support, China has been accused of underwriting a humanitarian scandal. The atrocities in Sudan have been described by the U.S. as ‘the worst human rights crisis in the world today’.

The government in Khartoum has helped the feared Janjaweed militia to rape, murder and burn to death more than 350,000 people.

The Chinese - who now buy half of all Sudan’s oil - have happily provided armoured vehicles, aircraft and millions of bullets and grenades in return for lucrative deals. Indeed, an estimated £1billion of Chinese cash has been spent on weapons.

According to Human Rights First, a leading human rights advocacy organisation, Chinese-made AK-47 assault rifles, grenade launchers and ammunition for rifles and heavy machine guns are continuing to flow into Darfur, which is dotted with giant refugee camps, each containing hundreds of thousands of people.

Between 2003 and 2006, China sold Sudan $55 million worth of small arms, flouting a United Nations weapons embargo.

With new warnings that the cycle of killing is intensifying, an estimated two thirds of the non-Arab population has lost at least one member of their families in Darfur.

Although two million people have been uprooted from their homes in the conflict, China has repeatedly thwarted United Nations denunciations of the Sudanese regime.

While the Sudanese slaughter has attracted worldwide condemnation, prompting Hollywood film-maker Steven Spielberg to quit as artistic director of the Beijing Olympics, few parts of Africa are now untouched by China.

In Congo, more than £2billion has been ‘loaned’ to the government. In Angola, £3 billion has been paid in exchange for oil. In Nigeria, more than £5billion has been handed over.

In Equatorial Guinea, where the president publicly hung his predecessor from a cage suspended in a theatre before having him shot, Chinese firms are helping the dictator build an entirely new capital, full of gleaming skyscrapers and, of course, Chinese restaurants.

After battling for years against the white colonial powers of Britain, France, Belgium and Germany, post-independence African leaders are happy to do business with China for a straightforward reason: cash.

With western loans linked to an insistence on democratic reforms and the need for ‘transparency’ in using the money (diplomatic language for rules to ensure dictators do not pocket millions), the Chinese have proved much more relaxed about what their billions are used for.

Certainly, little of it reaches the continent’s impoverished 800 million people. Much of it goes straight into the pockets of dictators. In Africa, corruption is a multi-billion pound industry and many experts believe that China is fuelling the cancer.

The Chinese are contemptuous of such criticism. To them, Africa is about pragmatism, not human rights. ‘Business is business,’ says Chinese Deputy Foreign Minister Zhou Wenzhong, adding that Beijing should not interfere in ‘internal’ affairs. ‘We try to separate politics from business.’

While the bounty has, not surprisingly, been welcomed by African dictators, the people of Africa are less impressed. At a market in Zimbabwe recently, where Chinese goods were on sale at nearly every stall, one woman told me she would not waste her money on ‘Zing-Zong’ products.

‘They go Zing when they work, and then they quickly go Zong and break,’ she said. ‘They are a waste of money. But there’s nothing else. China is the only country that will do business with us.’

There have also been riots in Zambia, Angola and Congo over the flood of Chinese immigrant workers. The Chinese do not use African labour where possible, saying black Africans are lazy and unskilled.

In Angola, the government has agreed that 70 per cent of tendered public works must go to Chinese firms, most of which do not employ Angolans.

As well as enticing hundreds of thousands to settle in Africa, they have even shipped Chinese prisoners to produce the goods cheaply.

In Kenya, for example, only ten textile factories are still producing, compared with 200 factories five years ago, as China undercuts locals in the production of ‘African’ souvenirs.

Where will it all end? As far as Beijing is concerned, it will stop only when Africa no longer has any minerals or oil to be extracted from the continent.

A century after Sir Francis Galton outlined his vision for Africa, the Chinese are here to stay. More will come.

The people of this bewitching, beautiful continent, where humankind first emerged from the Great Rift Valley, desperately need progress. The Chinese are not here for that.

They are here for plunder. After centuries of pain and war, Africa deserves better.

Source & Credits: Andrew Malone For The Daily Mail