Authorities keep arresting people said to be bosses of wildlife trafficking, but that isn’t making a dent in the problem.

In 2003, enterprising criminals in Southeast Asia realized that they could exploit a loophole in South Africa’s hunting laws to move rhino horns legally across international borders.

Normally, North Americans and Europeans account for the bulk of South Africa’s rhino hunting permits. But that year, 10 Vietnamese “hunters” quietly applied as well.

Hunters are allowed to transport legally obtained trophies across borders under various international and domestic laws. The Vietnamese hunters each returned home with the mounted horn, head or even whole body of a rhino.

Word spread. Though Vietnam and other Asian countries have no history of big-game sport hunting, South Africa was soon inundated with applicants from Asia, who sometimes paid $85,000 or more to shoot a single white rhino.

That represented the beginning of an illicit industry referred to as pseudo-hunting — a first step toward the rhino poaching crisis that rages today. And the story of one of its chief practitioners shows the lengths to which criminals will go to move wildlife contraband.

No one knows just how many rhino horns were actually sent back to Asia as purported hunting trophies.

South Africa has records of more than 650 rhino trophies leaving the country for Vietnam from 2003 to 2010 — goods worth some $200 million to $300 million on the black market. Vietnam, however, has corresponding paperwork for only a fraction.

By 2012, South African investigators had identified at least five separate Vietnamese-run criminal syndicates exploiting the pseudo-hunting loophole.

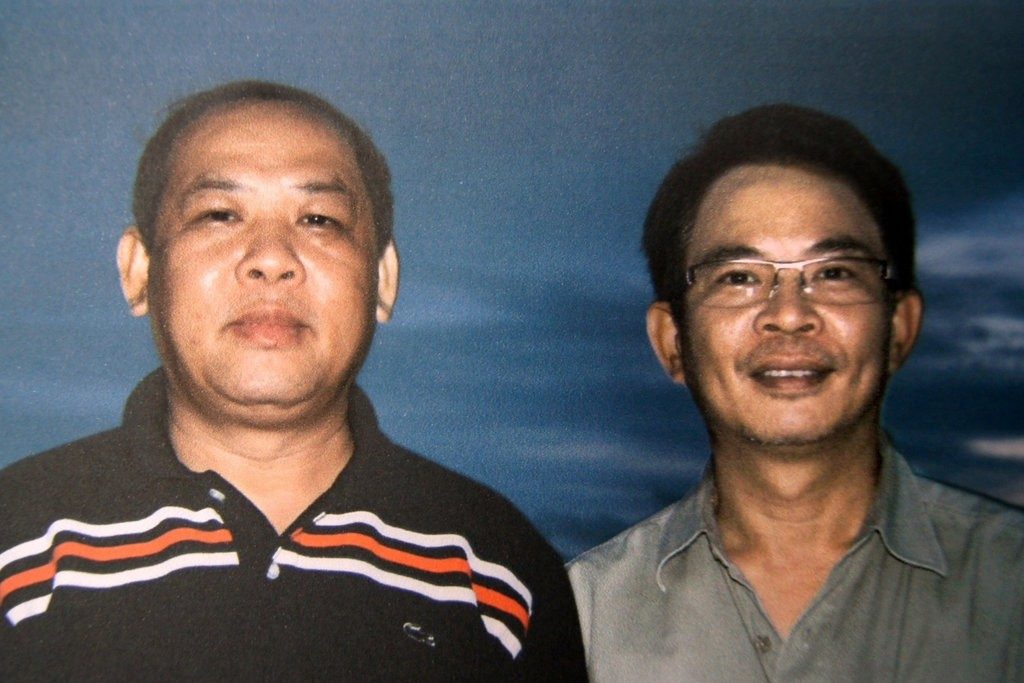

Chumlong Lemtongthai, a Thai citizen, and his band of gun-toting prostitutes were surely the most remarkable of those gangs.

To acquire more hunting permits, Mr. Chumlong hired more than two dozen women to pose as hunters. The women received around $550 just to hand over copies of their passports and to take a brief “holiday” with Mr. Chumlong and his men in South Africa.

Mr. Chumlong likely would have gotten away with the scheme were it not for Johnny Olivier, a fixer and interpreter in South Africa. Mr. Olivier worked for Mr. Chumlong, but after fifty or so rhino kills, his conscience began to nag at him.

“This is not trophies or whatever,” Mr. Olivier told me he recollected thinking. “This is now getting into slaughtering, purely for money. These rhinos are my nation’s inheritance.”

Mr. Olivier discussed Mr. Chumlong’s dealings with a private investigator, who began digging. The investigator eventually compiled 222 pages of evidence.

When the case went to court in 2012, South African prosecutors described Mr. Chumlong as the mastermind behind “one of the biggest swindles in environmental crime history.” To Mr. Chumlong’s shock, and that of many observers, he was sentenced to forty years in prison.

It was a punishment unheard-of in its severity, especially in a country with notoriously low rates of conviction for alleged wildlife crimes. Of 317 arrests related to rhino poaching in 2015, for example, just 15 percent resulted in guilty verdicts.

But Mr. Chumlong served nowhere near 40 years. In 2014, Mr. Chumlong’s sentence was reduced to 13 years in prison, plus a fine of about $78,000.

This month, South Africa granted Mr. Chumlong early release after serving six years. Amid an uproar of criticism from conservation groups and government officials, he was swiftly deported to Thailand.

It’s not often you get to talk to a man convicted of systematic rhino slaughter. I interviewed Mr. Chumlong at the Pretoria Central Correction Center on a sunny Sunday morning in October 2016.

The guards led me into a spartan office where I found Mr. Chumlong seated on a bench near the wall, wearing an orange jumpsuit with “Corrections” written in circular patterns all over it.

Wire-rimmed glasses framed his dark eyes, and his hair, once dyed black, was shaved short and gray, matching the stubble around his chin and upper lip.

I introduced myself, turned on my tape recorder and told him that I was there to hear his story. After some hesitation — he didn’t appreciate how the press had depicted him in the past, without even speaking to him, he said — he agreed to talk.

“Can you tell me about your involvement with rhino hunting?” I began.

In a gush of broken English, Mr. Chumlong told me that he was a legitimate businessman who recruited Asian tourists to hunt in South Africa. “I get tourists to shoot, I get commission,” he said. “I’m never poaching. I go legal way.”

He described having what he thought were legitimate hunting permits, only to be arrested by the South African police for fraud and railroaded into jail after signing what he believed was an agreement to pay a fine.

Soon enough, he was practically shaking, his eyes wide, his voice high.

“He said lie to me, my lawyer! Rhino farmer go home, me go to jail 40 years!”

The way he told it, it did sound possible that Mr. Chumlong had been a scapegoat for savvier criminals who took advantage of his ignorance to help get rhino horns out of the country.

According to South African and Thai authorities and conservationists, Mr. Chumlong’s boss was Vixay Keosavang, a Lao citizen once called the Pablo Escobar of wildlife trafficking. He has denied involvement in trafficking, and Mr. Chumlong told me he had not had any contact with Vixay Keosavang after his arrest.

“Vixay never talk. Only me, ‘kingpin,’” Mr. Chumlong scoffed. “Company, friend, family — never talk to me.”

Mr. Big doesn’t matter

Mr. Chumlong’s case illustrates one of the most profound obstacles to disrupting the international trade in illegal wildlife: the decentralized, constantly morphing networks along which poached goods are transported.

South Africa tightened its sport hunting rules after Mr. Chumlong was arrested, and in the overall story of the illegal wildlife trade, pseudo-hunting proved a “temporary sideshow,” as Ronald Orenstein, a conservationist, put it in his book “Ivory, Horn and Blood.”

Straight-up poaching and trafficking now dominate. Yet many of the players are still the same.

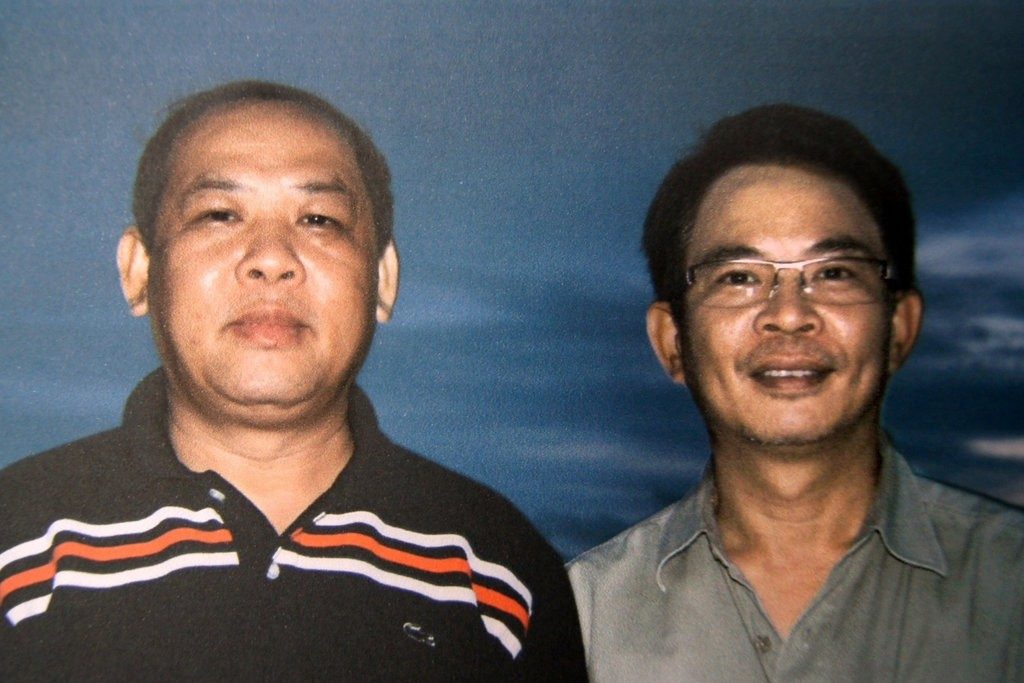

Again and again, associates of Mr. Chumlong and Vixay Keosavang from a decade ago, or longer, have turned up in wildlife trafficking cases, among them Bach “Boonchai” Mai, arrested by the Thai police earlier this year.

But because of the way the poaching and trafficking networks work, taking down any one of these supposed kingpins will not stop the illegal trade.

To get their prize, rhino poachers — who are often desperately poor local men living on the fringes of parks and reserves — tend to sneak in under cover of darkness, sometimes during the full “poacher’s moon,” as it’s often called.

Once in the park, they usually wait until first light to kill a rhino. Afterward, they may await well-organized pickups, or they may bury the horn for later retrieval. Others simply run home with the horn as quickly as they can.

After a horn — or a tusk, bag of bones, box of scales or other animal contraband — is smuggled out of a park, the goods are usually transferred along a chain of “runners” who take them to larger and larger cities.

At some point, Asian businessmen based in Africa are likely to get involved — generally Vietnamese bosses for rhino horn, Chinese bosses for ivory.A Thai woman hired by Mr. Lemtongthai to hunt rhino, according to South African investigators, posed with her trophy.Creditvia Julian Rademeyer

Once the contraband begins its trafficking journey, the route often isn’t direct. A China-bound ivory shipment may be sent first to Spain from Togo; a passenger carrying rhino horn may fly to Dubai before heading to Kuala Lumpur and then to Hong Kong.

This roundabout travel obscures the goods’ true origin and destination, and the route often reflects the placement of compromised officials who allow for a smooth journey.

“People who operate in the legal field — in government or in the transportation or wildlife industry — play a vital role in ensuring that rhino horn or any other wildlife contraband passes along the supply chain,” said Annette Hübschle-Finch, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cape Town’s Center for Criminology.

“They are the gatekeepers and intermediaries. They provide the link between the bush and the market.”

Trafficking bosses themselves are often also involved in legitimate and even well-known local businesses.

In the West, “organized criminals live in a somewhat parallel society,” said Tim Wittig, a conservation scientist at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. But among wildlife traffickers, “the big criminals are typically also big business people.”

“Usually, they’re involved in logistics-type businesses — trading or shipping companies, for example — or in commodity-based ones, which is why it’s easy for them to move things around,” he added.

These individuals are sometimes referred to as kingpins, a term that experts say is overused.

“In some ways, chasing after a Mr. Big behind it all is a bit of a myth,” said Julian Rademeyer, a project leader with Traffic, a conservation group, and author of “Killing for Profit: Exposing the Illegal Rhino Horn Trade.”

One of the most important characteristics of poaching and smuggling networks is their diversity, according to Vanda Felbab-Brown, an expert on international crime at the Brookings Institution in Washington.

While some networks are highly organized, others are completely dispersed. A dealer smuggling ivory out of an African port may not know the local boss overseeing poaching or the trader who eventually sells the contraband in Asia.

In the cartels run by just one or a few individuals, vacuums left by arrests are quickly filled.

That is why these convictions, even high-profile ones like Mr. Chumlong’s, usually have little effect on shutting down illegal trade — in wildlife, drugs or any other kind of contraband, Dr. Felbab-Brown pointed out.

Recent arrests

Three recent arrests for illegal wildlife trafficking have received wide attention among conservationists: Feisal Mohamed Ali, charged with trafficking in ivory in Kenya; Abdurahman Mohammed Sheikh, another alleged ivory trafficker in Kenya; and Yang Fenglan, Tanzania’s so-called queen of ivory. All have denied the charges and await trial.

But even if they were all eventually found guilty, Dr. Wittig noted, their trade would account only for a meager 10.9 tons of ivory over the past decade, or the equivalent of 1,500 elephants.

By Dr. Wittig’s estimate, the total amount they may have trafficked accounted for just 10 percent of African ivory smuggled over that period. Nor has poaching declined since those individuals were arrested.

“Arresting a few alleged wildlife-trafficking ‘kingpins’ may be a useful symbolic tool for promoting the importance and feasibility of strong enforcement to the general public,” Dr. Wittig said. But “it is not likely to be effective in actually saving protected wildlife, especially if done in isolation.”

Changing this largely depends on changing the way the world addresses illegal wildlife trade.

John Sellar, formerly chief of enforcement for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, has argued that we should instead just think of wildlife trafficking more simply as a crime, not a conservation issue.

But most of those tasked with fighting this type of crime are conservationists, rangers and wildlife managers. Mr. Sellar and other experts argue this job should instead be assigned to police, detectives, money-laundering experts and the courts.

That criminal groups dealing in wildlife tend to include multinational players further complicates investigations. Governments often do not share information or effectively collaborate across borders.Thai police officers arrested Bach “Boonchai” Mai in January on wildlife trafficking charges.

After decades of work, for example, Samuel Wasser, chair of the Center for Conservation Biology at the University of Washington, has developed a game-changing forensic method that allows experts to use DNA to determine the geographic origins of seized tusks, and thus to map poaching hot spots in Africa.

Dr. Wasser could produce a map showing officials and law enforcement exactly where they need to go to shut down the ivory trade in its current form. Yet most countries don’t get around to sending him samples of poached ivory for a year or more after a seizure. Some refuse to share any samples at all.

“That’s the hardest part for me, seeing how powerful a tool we have. Yet countries are so reluctant to let us use it,” Dr. Wasser said.

Even officials within a country plagued by poachers may not cooperate. Police officers don’t talk to customs officials who don’t talk to rangers. Rangers don’t have access to policymakers who don’t consult conservation groups.

“The intelligence environment is like spy-versus-spy,” said Ken Maggs, head ranger at Kruger National Park in South Africa.

Breaking up the decentralized criminal networks of poachers, experts say, will require the building of new networks among those who oppose the decimation of animal species. Arresting a few “kingpins” here and there will never be a substitute.

“If the genie in the bottle were to grant me just one wish to combat international wildlife crime, I would ask that everyone work more collaboratively,” Mr. Sellar has written.

“I remain convinced, utterly convinced, that we would make major inroads into combating international wildlife crime if we could only get our act together.”

Rachel Nuwer is a regular contributor to Science Times and the author of “Poached: Inside the Dark World of Wildlife Trafficking,” published on Sept. 25, from which this article is adapted.

Source: NewYorkTimes