As the frozen fish defrosts under the hot Kenyan sun, fishmonger Mechak Juma prefers not to tell his customers that it has come all the way from China.

We are at the largest fish market in the city of Kisumu, on the eastern shores of Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest lake.

A scene of hustle and bustle, business is booming for the traders, but very little of that money now goes to the local fishermen.

As fish stocks in Lake Victoria have plunged over the past two decades, and prices have risen sharply as a result, cheap farmed Chinese imports are increasingly filling the gap.

“People don’t want to buy Chinese fish because they don’t trust the [farmed] production process, but we don’t have much of a choice,” says Mechak, standing next to a big wicker basket of whole Chinese tilapia fish.

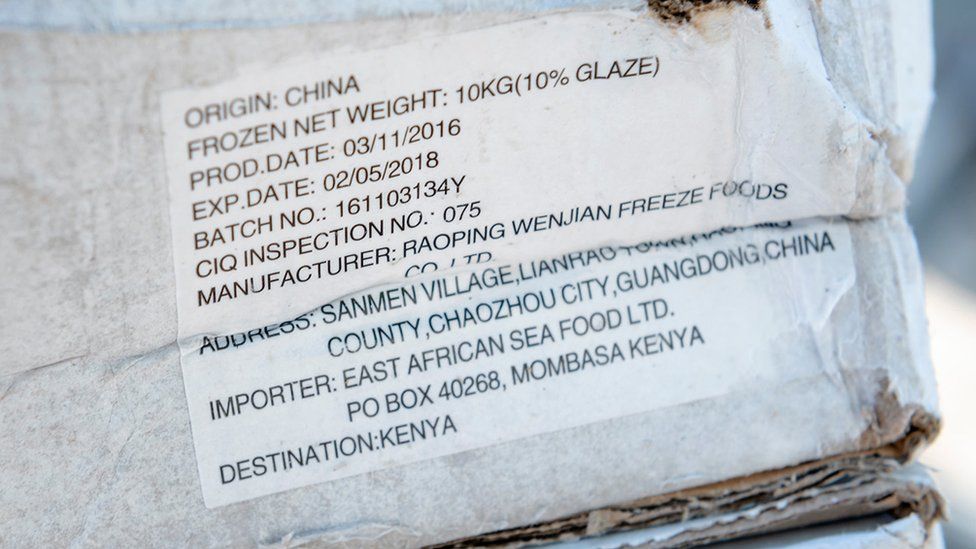

The trampled cardboard boxes used to ship the frozen fish 8,000 km (5,000 miles) are stashed away in a corner, and the fish itself is more than two years old.

It will expire in less than a month, according to the dates on the boxes.

“People prefer to buy local fish, but we earn nothing on local fish now,” says the 29-year-old.

“Only by selling Chinese fish am I able to earn enough money to feed my family.”

Fish catches from Lake Victoria have plummeted by more than half over the past two decades, due to overfishing and pollution. Over the same period Kenya’s population has doubled.

Vast stretches of water hyacinths, an invasive weed, along the shorelines, have also caused severe problems for the country’s fishermen.

The thick, interwoven carpet of the plants means that smaller boats can struggle to get out to clear water.

Kenya’s Lake Victoria fishermen now bring in an estimated 140,000 tonnes of fish per year, little more than a quarter of the 500,000 required.

Chinese companies and their Kenyan partners seized the opportunity, and are now said to be exporting more than $17m (£13m) of fish to Kenya annually, more than double the amount three years ago.

It was an easy gap for the Chinese to fill, because the freshwater fish that they farm on a vast scale - tilapia - is from the same broad species that Kenyans mostly catch in Lake Victoria. So for Kenyan consumers the fish look and taste very similar.

The Chinese fish is just considerably cheaper, selling for as little as $1.70 per kg, compared with about $5 per kg for the local catch.

For Kenyan fisherman Frederike Otieno, it is a hopeless situation.

“While we spend many nights on the lake and lose a lot of money on fuel, we have to compete with this cheap Chinese farmed fish that floods the market,” says the 36-year-old.

The father of three says that sometimes he cannot sell all his catch.

A fisherman for 10 years, he says he used to earn about 3,000 Kenyan shillings ($30; £23) per day, but that has now fallen to little more than 400 shillings.

In November last year, the Kenyan government moved to try to protect the Lake Victoria fishing industry by imposing an import ban on foreign tilapia.

But the restrictions were lifted in January after China’s ambassador to Kenya, Li Xuhang, referred to the ban as a “trade war”.

It was also reported that China had threatened to freeze funding for a new railway line connecting Kenya with Uganda, Rwanda and South Sudan.

However, the official explanation from Kenya’s Department for Fisheries for the U-turn was that “a huge shipment of [Chinese] fish was held up at the port of Mombasa, negatively impacting local supplies”.

What Kenyan authorities are continuing with is efforts to improve fish stocks in the lake, for example, by arresting fishermen who fish too close to the breeding areas near the shores to save on time and fuel.

But this deterrent continues to increase prices in the short term, as fisherman have to travel further out into the lake.

The biggest importer of Chinese fish in Kenya is a company called East African Sea Food. Its director, John Musafari, says that while the farmed Chinese tilapia is high quality, the low prices are possible because the fish is fed on rice bran, which is cheap and plentiful.

This bran is the hard outer layer of each rice grain, which is removed in China before the rice is sold to consumers.

Mr Musafari adds that fish farming has not taken off in Kenya because fish feed “is extremely expensive” in the country, due to it currently being made from maize, which is also the country’s staple food.

He wants to see more investment in the development of cheaper fish feed in Kenya. “That could really boost the country’s aquaculture,” he says.

Others in Kenya are very happy with the growing reliance on Chinese fish imports, such as Simon who helps to transport the boxes across the country.

“Thanks to this Chinese tilapia, poor people can now eat nutritious protein-rich fish as well,” says Simon, who declined to give his full name. He now makes $300 a day, which for many Kenyans is more than their monthly salary.

Yet for Edward Oremo, a Kenyan fisheries official, it will ultimately mean the end of commercial fishing on Lake Victoria.

“As long as Chinese imports continue… fishermen will be driven to despair, and Lake Victoria will be empty [of fishing boats] in less than 50 years.”

All pictures copyright Jeroen van Loon.

Source: BBC